The Konyak tribe of Nagaland is one of the most populous and major tribes of Nagaland. They are mostly found in the Mon district of Nagaland as well as in Arunachal Pradesh, Myanmar and Assam. Traditional practices that set the Konyaks apart are: headhunting, gunsmithing, facial tattoos, iron-smelting, brass-works, and gunpowder-making. However, the practice of headhunting is no longer prevalent among them due to their conversion to Christianity and exposure to modern education. Let’s explore more about the Konyak tribe of Nagaland in this blog.

History of Konyak Tribe of Nagaland

The term ‘Konyak’ is believed to have been derived from the words ‘Whao’ meaning ‘head’ and ‘Nyak’ meaning ‘black’ translating to ‘men with black hair’. The Konyaks are Mongoloid in origin. Linguistically, the Konyaks come under the Naga-Kuki group of the Tibeto-Burman family with each village having its own dialect. The dialect of the Wakching village of Mon district is commonly used as the medium of communication among the Konyak tribe of Nagaland. The estimated population of the Konyak tribe is approx 320,000. Before the advent of Christianity in Nagaland, the Konyaks were believers of “Animism” worshipping different objects of nature. About 95% of the population follows the Christian faith now.

Types of Konyak: Thendu and Thentho

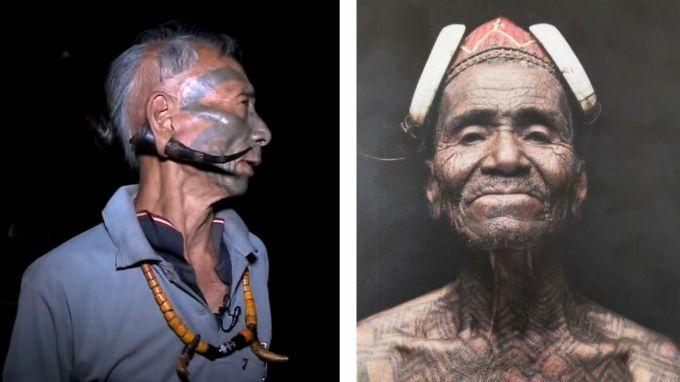

The tribe is broadly distinguished into two groups –Thendu, which means the ‘Tattooed Face’ and Thentho meaning the ‘White face’. The Thendu group is mostly found in the central part of the Mon district and the Thenko group is mostly in the upper part and the lower part of the district in the Wakching area. There were differences between the two groups in their material lives, social classes, and cultural and linguistic lines. While the practice of tattooing could be found in both Hindu and thenkoh groups, faces were tattooed only in the Hindu group.

Unique Governance of the Konyak Tribe of Nagaland

It is said that when the Konyak migrated first to Chui village of the Mon district of Nagaland, they had a big council meeting to decide whether they should have an Angh system or a democratic system. Those who favoured Angship settled in lower areas of Mon district such as Mon town, Tizit and Naginimora area. Those who were against it occupied the upper areas such as Longching, Chen, Mopong and Tobu and they had some form of democratic rule.

The Anghs of Konyak Tribe

A unique feature of the Konyak tradition is the practice of the Angh system. There are two different kinds of Anghs among the Konyaks, Pongyin Angh or Anaghtak Anghyong (the Great King or Monarch/Chief) and Angh (small king).

The Pongyin Angh is found only in some Thendu villages. The Anghs in the thendu villages were very powerful with the final authority on any decision-making for the entire village resting on him. In a village where there is no Pongyin Angh, an Angh is appointed. Such a village becomes a subject village to the Pongyin Angh from whose family the Angh is appointed. The Angh and the village council consisting of an elder from nokphong (clan) take care of the village administration.

The Angh (King) of Konyak had under them villages varying from 4-21 paying tributes to the great Ang. Each village had one Ang but above them all stood the great Angh who had the power to interfere in the affairs of other Angs under him. The term Angh (King) is found only in Wakching village; the rest of Konyak tribe villages use the term Wang.

At present, under Article 371 (A) of the Indian constitution, the localised structures of power maintain the authority over customary laws and procedures of the ownership and transfer of land and its resources along with others.

How To Become an Angh in Konyak Society

An Angh may marry as many women as his wealth and influence permitted. But he has to keep one among them as principal wife. Children through the principal wife enjoy higher positions and the son of such wife is eventually the chief. So, Anghship is hereditary. The most characteristic feature of the Konyak chieftainship is the selection of the principal wife only from an Ang family of another village.

How Many Anghs are there in Nagaland?

Altogether, there are eight “Chief Anghs” within Mon District, namely (1) Chui (2) Mon (3) Tangnyu (4) Shangnyu (5) Longzang (6) Shengha Chingnyu (7) Longwa & (8) Jaboka. The Chief Anghs of these villages rule over a group of satellite villages under them, some of which are in Arunachal Pradesh and Myanmar but have strong customary and traditional relationships with the rest villages in the Mon District. The Konyak tribe is distributed between India and Myanmar. However, their customary laws remain the same and transcend international boundaries.

Festivals of Konyak Tribe of Nagaland

Festivals occupy an important place in the lives of the Konyaks. The three most significant festivals were Aolingmonyu, Aonyimo and Laoun-ongmo.

Along Monyu festival of the Konyak Tribe: It is one of the greatest festivals of the Konyak tribe. The entire Konyak community of Nagaland observes this festival in the first week of Aoleng Lee (April). Along Lee is observed after the completion of the New Year beginning with spring when the riot of flowers in every hue starts to bloom. The significance of this festival is to ask the Almighty God to bless them with a bountiful harvest. This festival spreads for 6 days and each day carries a different significance. Its religious significance is to appease (Kahwang/ Yongwan) God for a prosperous harvest.

The Aonyimo is celebrated in July or August with pomp and gaiety after the harvest of the first crops like — maize and vegetables. The Laoun-Longmont is a festival of thanksgiving and is celebrated after the completion of all agricultural activities.

Traditional Attire of the Konyak Tribe

Konyak men wear conical red headgear adorned with wild boar canines and Hornbill bird feathers, complemented by brass necklaces featuring miniature human head pendants. Some elderly Konyak men opt for horn-shaped ear plugs and accessorize with handwoven shawls and a snug red or black waist belt.

Konyak Women showcase captivating and vibrant jewellery crafted from glass and seed beads, along with conch shells. Their attire includes intricate headpieces, necklaces, waistbands, and earrings in shades of orange, yellow, red, and blue. Konyak women don wrap-around skirts, predominantly in black with vibrant green, blue, red, and yellow stripes. The skirt lengths vary, ranging from knee-length to ankle-length, accompanied by elegant shawls.

Tribal Dormitories of the Konyak Tribe

Similar to the other Naga tribes the Konyaks had the system of Morungs or Baan. These were bachelors’ halls where discussions and decisions regarding their social, political and economic life were taken by men and young boys initiated into the way of living of the village.

The Morong is an institution in itself. In the olden days, new generations were taught fighting and defence tactics around its campus. It also used to be a common armoury for the village. It was also used as a guardhouse during times of war when warriors stayed in it. That was why the Morung was built next to the village gate or at the strategically most advantageous place. Heads of the defeated rival chiefs and enemies were adorned and showcased here.

In the past few decades, Morungs as a physical structure disappeared in most villages. Only a few old Morung have been maintained and have now become a much-looked-after part of the cultural heritage of the respective village.

The Head-hunting Practice of the Konyak Tribe

The headhunting practice of the Konyak tribe of Nagaland has been taught to the younger generation by the older generation since time immemorial. It is said that the Konyak Tribe bring home the heads of enemies defeated. The person who kills and carries the head is chosen as the leader of the pack. It carries a special significance and status symbol.

Another version of the oral history of the Konyak tribe says that the heads of the defeated people are auspicious for the villagers and wards of evil. Besides human skulls, heads of game animals and other kills and sacrifices such as wild buffalo, and boar are also preserved the show strength and custom. For the Kanyak, these are trophies and these trophies are collected and preserved in a special home called Morong’/Morung.

Contrary to popular myth, the tradition of headhunting was done neither for sport nor cannibalism. The glory attached to headhunting trophies and tattoos was more about lionising the men who defended their land and territory from encroachers, just as modern -day defence personnel are glorified with medals and admiration after standing up to their enemies.

Does the Konyak Tribe of Nagaland Still Practice Headhunting?

It’s important to note that headhunting was not a universal practice across all Naga tribes, and it wasn’t exclusive to the Konyak tribe either. It is practised by the Wancho tribe also. Today, the Konyak tribe, like many other Naga tribes, has embraced Christianity and transitioned away from their traditional practices, including headhunting. The practice of headhunting has now become a part of history and folklore, remembered as an integral but controversial aspect of their cultural heritage.

Huh tapu (Tattooing) of the Konyak Tribe of Nagaland

The Konyak tribe of Nagaland tattooed their face and other parts of the body as only when they attain certain criteria or fulfil certain norms of the society. According to the cultural norms, boys have to attain an age of 8 years and girls have to attain an age of 11 years for tattooing on their body parts. Different designs signify different social statuses such as Ahng (Elderman/King), Pin (Commoner) and the warriors. Facial tattoos are mostly done by adult males when they come back from the war after a hunting expedition.

It is to be noted that the practice of tattooing could be found in both Hindu and thenkoh groups of the Konyak tribe, faces were tattooed only in the Hindu group.

Meaning of the Tattoo

Tattoo on the body signifies different symbols and meanings and there is a significant difference between the tattoos of men and women. A tattoo on the calf of a girl’s leg signifies she is mature enough to perform any activities in society. The tattoo on her arm signifies she is engaged in marriage. A tattoo on a boy‟ ‘s chest, arm and face signifies that he is a mature man and right to perform and participate in the activities of society.

Tattoo by Headhunters of Konyak Tribe

A man is regarded as a warrior when he brings the head of his enemy to the village and gets a distinctive and dignified facial tattoo. He is respected by all; he is also invited to feast in different houses in the village. During rituals or celebrations, he will raise the slogans of peace, war and victory. However, the unique facial tattoos and other parts of the body tattoo are declining very fast in the Konyak tribe of Nagaland. Once upon a time, facial tattoo was a form of social status and achievement among the older generations of the Konyak society but now it is a form of fashion and style among the Konyak tribe of Nagaland.

Making of an Indigenous Gunpowder by Konyak Tribe

The tradition of gunpowder making by the Konyak tribe is locally known as the ‘Ghat lineup’. Even before the arrival of the British, the use of guns and gunpowder was widely prevalent among the Konyak tribe of Nagaland. Gunpowder is widely used on different occasions such as in war, hunting, festivals, and during the death of a person.

The materials used for gunpowder are charcoal derived from Omah wood (Trema orientalis) and a salt, “potassium nitrate‟. The components in gunpowder are simple and its preparation decides the quality of the gunpowder. First, the wood (Omah) is burned down completely and the charcoal obtained from it is kept separately to cool down, it is then pounded and ground into powder using a special tool like a pestle. The unwanted particles are separated from charcoal powder and salt in a ratio of 3:10.The mixture is then heated again and again until it is dried up; the end product is kept in a dry and warm place that is free from dust or any other particles that could lower the potential and the quality of the gunpowder.