Assam has long been a threshold land—between hills and plains, tribes and kingdoms, the seen and the unseen. For centuries, Tantric practices flourished here not as secret cults alone, but as living traditions tied to land, fertility, power, and protection. Unlike classical temple of Hinduism, Assam’s Tantra absorbed indigenous Tibeto-Burman beliefs, animism, and fierce mother-goddess worship. Blood offerings, human & animal sacrifice and the idea that divine power must be fed were central to this worldview. In this landscape, goddesses were not distant ideals—they were present, hungry, protective, and dangerous.

It was within this spiritual ecology that the Tamreswari Temple rose, a shrine remembered as much for its splendour as for its terror.

About Tamreswari Temple

Eight miles northeast of present-day Sadiya town, on the banks of the Dhal River (ঢল নদী), once stood the Tamreswari Temple—now erased from the earth, but not from memory.

To the Deuris, the goddess of this temple was Peshasi. To the Chutiyas, she was Dikkaravasini. Among the Bodo-Kachari tribe, she was Kechaikhati Gosani—a name that still sends a shiver down the spine. Kechaikhati in Assamese means “the eater of raw flesh.” Others called her Tamreshwari Mai.

No one today can say with certainty who first built her shrine—the Kacharis or the Chutiyas. What is known is that this was a prehistoric sacred site, later rebuilt in the 15th century by Chutia kings. It stood at the heart of the Chutia Kingdom, a nexus where spiritual authority, political power, and community life merged into one.

The temple embodied a rare syncretism: indigenous tribal rituals layered with Hindu Tantric symbolism, creating a form of worship unique to medieval Northeast India.

Temple Architecture

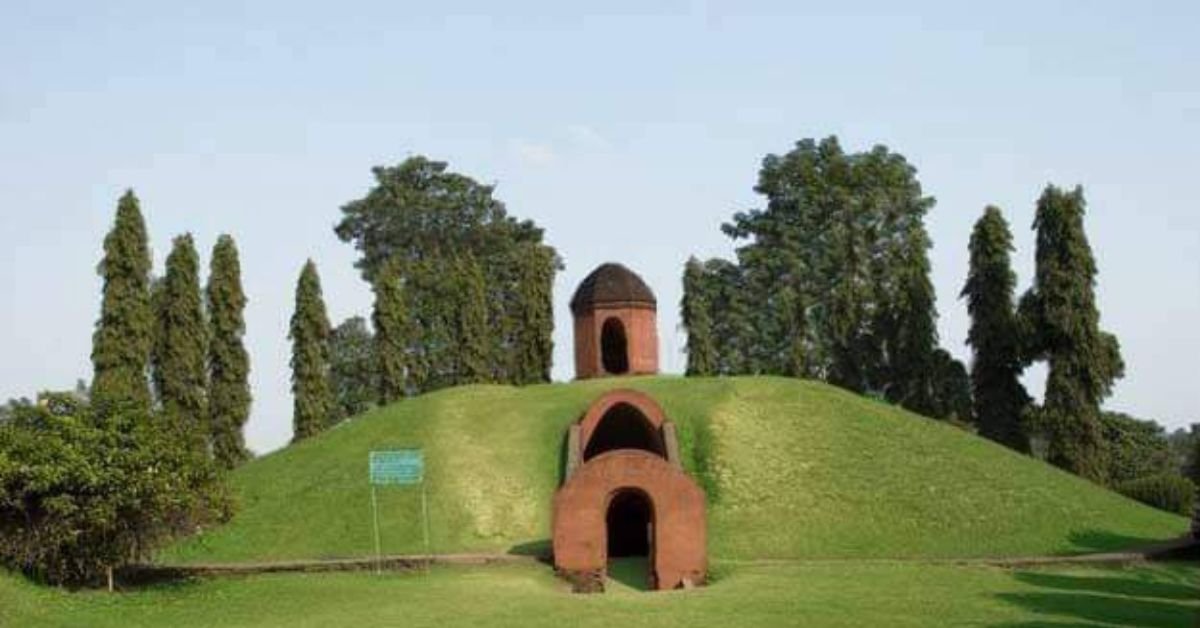

Though no physical remains survive today, memory and archaeology paint a vivid picture. The temple was constructed of granite stone, its gates adorned with intricate carvings. At the entrance stood a stone elephant, its tusks plated with silver—silent guardians of the goddess within.

The roof was made of copper, giving the temple its name. Tam or Tamra means copper in Assamese, a metal associated with power, heat, and divine energy. Surrounding the shrine were brick walls measuring roughly 130 feet by 200 feet, enclosing not just a temple but a world set apart.

In front of the western wall stood a small, three-legged stone. To the uninitiated, it may have appeared insignificant. To those who knew, it marked the shadow of a far darker ritual.

For this was a temple where human sacrifice was performed—once every year.

The Chosen One

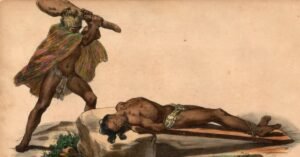

The sacrifice was not random chaos; it followed a grim order shaped by belief and state control. In earlier times, it is said that human offerings were regularly made to appease the goddess. Later, under Ahom rule, restrictions were imposed. Only those sentenced by the ruler were permitted to be sacrificed. But justice did not always supply a victim.

So the rule changed.

Each household was required to offer an innocent young man. Once chosen, the youth was not treated as a criminal. He was separated from the world and kept in another temple for several days. He was well fed, nurtured, and cared for—not out of mercy, but reverence. He was becoming an offering, transformed from a man into something sacred.

However, certain boundaries were strictly maintained. Brahmins and members of royal families were never sacrificed. People considered of ‘lower’ caste, Muslims, and women were deemed unworthy of offering to the goddess.

The Secret Passage

On the appointed day, the village would sense it, even if no drum was beaten. The chosen one was dressed in fine clothes, adorned with gold and silver ornaments. He did not walk as a condemned man, but as a ritual participant in a destiny older than the kingdom itself.

Led by the priest, he was taken through a secret passage—hidden from all eyes. No one else was allowed to follow. Near the temple lay a well. There, the ornaments and clothes were removed. The final offering was made in silence. The body fell into the depths of the well, swallowed by darkness. The severed head was placed alongside others, arranged before the temple as proof that the goddess had been fed.

Blood was not murder here—it was theology.

When the Blood Stopped Flowing

The practice of human sacrifice was finally abolished during the reign of Ahom King Swargadeo Gaurinath Singh (1780–1794 AD). The decree marked a profound rupture between ancient belief and emerging moral authority.

But not everyone accepted the change.

According to Deuri tradition, the Ahoms lost their kingdom because they stopped human sacrifice. To them, the fall of a dynasty was not political failure—it was divine punishment.

Conquest, Desecration, and Disappearance

The decline of the Tamreswari Temple began much earlier, in 1524, when the Ahoms conquered Sadiya. Under King Suhungmung, the Chutia ruler Nityapal was defeated, and the kingdom annexed.

The Assam Buranji records that the temple was dismantled and desecrated, its destruction a symbolic assertion of Ahom dominance. The priests were dispersed, though some Deuris continued their worship in secrecy, returning to the ruins under cover of ritual memory.

Nature completed what conquest began. The floods of the Brahmaputra and its shifting channels likely erased the remaining traces. Today, nothing stands where the copper roof once caught the sun.

The Goddess Who Refused to Die

Yet Tamreswari did not vanish.

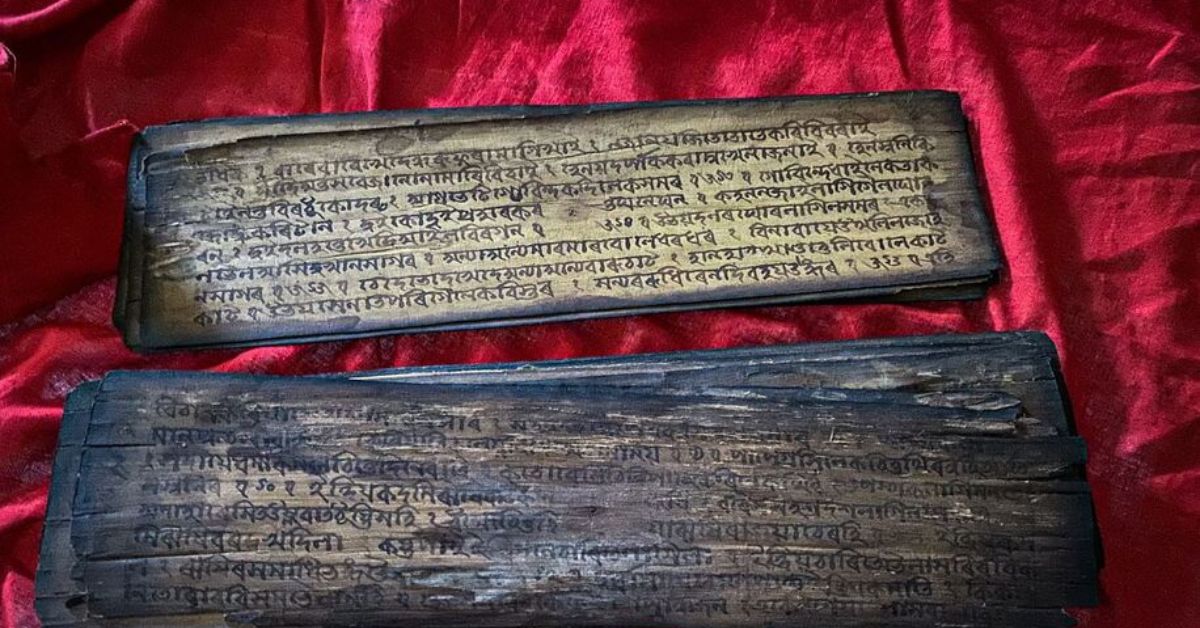

Four kinds of Deori priests once served the temple. The Bar Bharali and Saru Bharali collected dues and arranged animal sacrifices. The Bar Deori (Deori Dema) and Saru Deori (Deori Surba) performed rituals and sang sacred hymns.

Their descendants still remember.

Across Lakhimpur and Dibrugarh, relocated shrines bear the name Tamreswari Temple. Annual festivals like Bihu continue to carry echoes of the old goddess, woven quietly into dance, song, and offering.

The temple is gone. The sacrifices have ended. But in Assam’s collective memory, the Tamreswari Goddess still waits—at the edge of history, where belief once demanded blood.