Hajo, a sacred town in Assam’s Kamrup district, stands as a rare symbol of religious harmony where Hinduism, Islam and Buddhism coexist side by side. Hajo is blessed with scenic hills, serene wetlands and centuries of spiritual legacy. From the revered Hayagriva Madhava Temple and the Buddhist belief of Buddha’s nirvana to the sacred Islamic shrine of Poa Mecca, the town reflects a deep-rooted tradition of faith, tolerance and cultural unity. In this blog, we will discuss why Hajo remains one of Assam’s most treasured pilgrimage and heritage destinations.

Geography of Hajo Town

Hajo, located in the Kamrup district of Assam, stands as one of the most remarkable sacred towns in India where Hinduism, Islam and Buddhism coexist in rare harmony. Situated on the northern bank of the Brahmaputra River, about 22 kilometres west of Guwahati, Hajo is not only a pilgrimage centre but also a destination of immense natural beauty, cultural depth and historical significance. Over centuries, this sacred landscape has evolved into a symbol of religious tolerance and shared heritage, making Hajo a priceless cultural asset of Assam.

Origin of the Name Hajo

It is named after Koch Hajo, a Koch tribal chief of the early 16th century. Linguists trace the name Hajo to the Bodo language words “ha” meaning land and “jo” meaning high or hill, together signifying a “high place.” This etymology aptly reflects Hajo’s geography, characterised by hillocks such as Manikuta, Garudachala and Madanachala rising gently near the vast Brahmaputra. The murmuring Lakhaitara stream, scenic ponds, and the tranquil Panikhaiti wetland add to the town’s serene charm. The harmony between river, hills and water bodies bestows upon Hajo a unique natural grace that enhances its spiritual aura. The place was known by various names, such as, Apunarbhava, Vishnupuskara, Manikutagram, Shujabad etc.

Historical Evolution of Hajo

Hajo’s history is both ancient and multifaceted. During the Pala dynasty around the sixth century CE, Hajo emerged as a major religious centre, with the initial construction of the Hayagriva Madhava Temple believed to have begun during this period. In 1583 CE, Koch king Raghudeva reconstructed the temple after the earlier structure collapsed. Subsequent Ahom rulers, notably Pramatta Singha and Kamaleswar Singha, carried out conservation and expansion works, strengthening Hajo’s religious prominence.

Inscriptions, copper plates and royal charters provide concrete evidence of these contributions. Ancient texts such as the Kalika Purana, Markandeya Purana and Yogini Tantra mention Hajo by various names including Manikuta, Vishnupuskara and Suryakshetra. Buddhists referred to it as Cham-cho-dam, while the Mughals called it Shujabad. These varied names reflect Hajo’s layered cultural identity. Strategically located near Guwahati, Hajo also played a military role during Mughal-Ahom conflicts, especially after Ahom king Rudra Singha recaptured Guwahati in 1682.

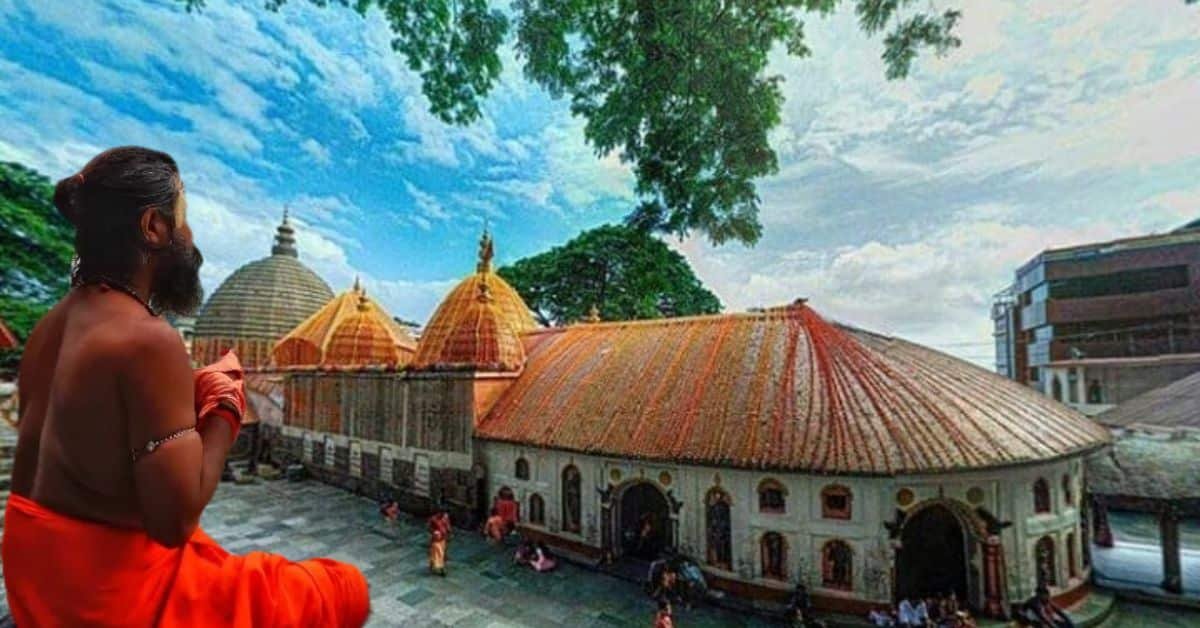

Hayagriva Madhava Temple: The Spiritual Heart of Hajo

The Hayagriva Madhava Temple, perched atop Manikuta hill at a height of nearly 300 feet, is the principal religious centre of Hajo. Dedicated to Lord Vishnu’s Hayagriva avatar, depicted with a horse’s neck, the temple is deeply rooted in Hindu mythology. According to the Kalika Purana, Lord Vishnu assumed the Hayagriva form to retrieve the stolen Vedas from demons Madhu and Kaitabha, killing them at this very site.

The Hayagriva Madhava Temple’s architecture follows the Nagara style with Pancharatra method, showing a unique blend of Hindu and Buddhist art in its vimana, antarala and mandapa. The sanctum houses idols of Hayagriva Madhava, Budha Madhava, Chalanta Madhava, Vasudeva and Garuda. The Chalanta Madhava idol, associated with a legend of movement underground, is ceremonially taken out during festivals, generating immense devotional fervour. Its base features 124 intricately carved elephants symbolising strength and support, while outer walls depict Vishnu’s ten avatars, including Buddha as the ninth avatar.

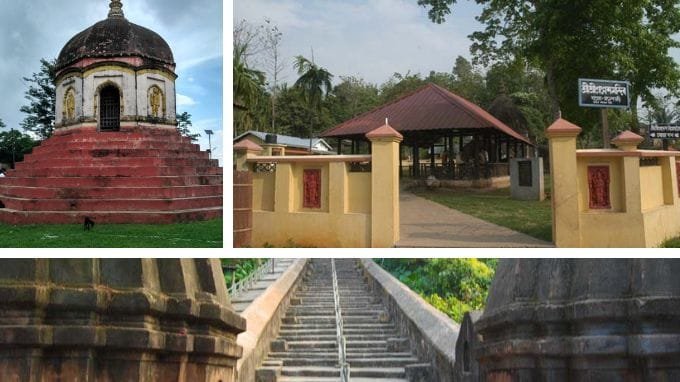

Certain motifs of the original work, particularly a row of caparisoned elephants relief, encircling the building, appear to be specimens of buddhist architecture. The elephant motif is identical to the decorative style of the cave temple at Ellora. There is another temple nearby, It is also called Daulgriha and was constructed by Ahom King Pramatta Singha.

Certain motifs of the original work, particularly a row of caparisoned elephants relief, encircling the building, appear to be specimens of buddhist architecture. The elephant motif is identical to the decorative style of the cave temple at Ellora. There is another temple nearby, It is also called Daulgriha and was constructed by Ahom King Pramatta Singha.

A number of stone images another things mostly in demolished condition are lying scattered in the precinct of the temple.Among these a few stone slabs with lion motif are the most remarkable pieces of architecture. These are said to the parts of an Ashokan pillar installed to the original Buddhist chaitya. Another piece of art is one Simhasana. The simhasana was decorated with winged lions made of ivory, in its four corners. Today the simhasana is not there but the broken pieces are lying unnoticed in an interior room of the temple.

Below the temple is a large pond named Apurnakumbha, where devotees wash their hands and feet before entering.  The fish and tortoises in this pond are considered symbols of Vishnu’s Matsya and Kurma avatars. At the temple entrance, a Hanuman statue and the lion gate enhance its artistic beauty.

The fish and tortoises in this pond are considered symbols of Vishnu’s Matsya and Kurma avatars. At the temple entrance, a Hanuman statue and the lion gate enhance its artistic beauty.

Daily morning puja, evening aarti and offerings during special festivals are traditionally observed.During Janmashtami, Dolotsav and Magh Bihu, the gathering of devotees creates a festive atmosphere. The hilly surroundings and the natural beauty of the Brahmaputra evoke profound peace and spirituality in pilgrims’ minds. The temple management is in the hands of local families who have maintained this tradition gen-erationally. Their devotion and faith preserve the temple’s sanctity. Some folk-lores associated with the temple’s history deepen its mythological significance. For instance, one legend says the idols first appeared in a dream, leading to the temple’s construction here. This combination of as-pects establishes the Hayagriva Madhava Temple as the spiritual heart of Hajo.

Hajo: A Sacred Buddhist Centre

Beyond Hindu devotion, the Hayagriva Madhava Temple is equally sacred to Buddhists. Tibetan and Bhutanese Lama communities believe that Gautama Buddha attained nirvana at this site. They worship the Budha Madhava idol (picture given above) as Mahamuni Buddha, making Hajo a rare shared pilgrimage space. The simultaneous chanting of Buddhist mantras and Hindu shlokas creates a profound spiritual confluence, reinforcing Hajo’s identity as a centre of religious harmony.

Poa Mecca: The Islamic Heritage of Hajo

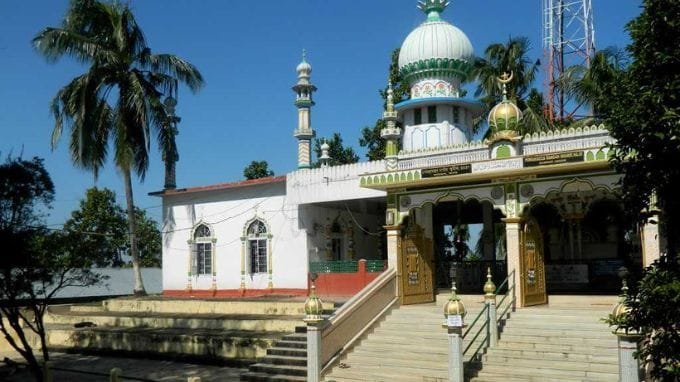

For Muslims, Poa Mecca is one of the most sacred Islamic sites in Assam. Located atop Garudachala hill, it is the mausoleum of Sufi saint Giyasuddin Auliya, who arrived in Assam in the 13th century to spread the message of Islam through compassion and service. Folklore suggests that soil from Mecca was used in constructing the dargah, giving rise to its name “Poa Mecca,” meaning “one-quarter of Mecca.” Devotees believe that visiting this site grants one-fourth the spiritual merit of visiting Mecca.

During the Mughal period, Lutfullah Shirazi constructed a mosque here in 1657, regarded as Assam’s first mosque. The Urs festival held annually during the Assamese month Magh (mid January) attracts devotees across faiths, with Sufi songs, zikr and qawwali fostering a spirit of peace and unity.

Its architecture features fine Mughal-style carvings and dome construc-tion. Floral designs and Quranic verses carved on the walls enhance its artistic beauty. The dargah environment is very peaceful, and its surrounding hilly land-scape evokes deep spirituality in devotees. Fakirs and paiks from nearby Fakirtola village maintain the dargah, exemplifying social harmony.

Architectural Brilliance and Pancha-Tirtha Tradition

Hajo’s architecture is a living testament to Assam’s artistic heritage. The blend of Hindu, Buddhist and Islamic styles is evident in temple sculptures, pointed arches influenced by Bengali Islamic design, and Mughal elements at Poa Mecca. Hajo is also known as Pancha Tirtha (পঞ্চ তীৰ্থ) Nagari, housing five sacred centres—Hayagriva Madhava, Kedar, Kamaleswar, Kameshwar and Ganesh temples.

The Kedar Temple on Madanachala hill, famous for its Ardhanarishvara lingam, draws thousands of devotees during Shivaratri. The carvings around Kedar’s lingam depict various scenes from Shiva-Parvati’s life. The nearby Madan Puskara pond is religiously significant; bathing there is believed to purify devotees.

Neo-Vaishnavism, Satras and Cultural Life

The influence of Srimanta Sankardeva and Madhavdeva’s neo-Vaishnavism is deeply embedded in Hajo’s cultural life. Dhoparguri Satra, where Madhavdeva staged Rukmini Haran, marks a milestone in Assamese cultural history. Satras in and around Hajo continue to nurture traditions of naam-kirtan, borgeet and devotional theatre (bhaona).

Handicrafts, Folklore and Living Traditions

Hajo is also a centre of rich handicraft traditions. Bell-metal works, pottery, wood carving and floristry reflect the skill of local artisans. Folklore associated with sites like Duwani-Muwani hill and Hargauri Temple further enriches the cultural landscape. Festivals and village fairs keep these traditions alive while strengthening community bonds.

Tourism Potential and Environmental Concerns

With its scenic Brahmaputra views, wetlands ideal for birdwatching, vibrant festivals and spiritual diversity, Hajo holds immense tourism potential. However, challenges such as pollution, illegal encroachment and unplanned urbanisation threaten its heritage. Sustainable tourism, conservation efforts and community participation are essential to protect this sacred town for future generations.

Conclusion: Preserving a Timeless Heritage

Hajo is more than a pilgrimage town—it is a living symbol of India’s pluralistic ethos. Its tri-religious heritage, historical depth, architectural brilliance and cultural vibrancy establish it as a world-class destination. Through responsible conservation and thoughtful promotion, Hajo can continue to inspire harmony, spirituality and cultural pride for generations to come.

FAQS

Q: What makes Hajo a unique symbol of religious harmony in India?

A: Hajo is unique because it beautifully unites Hinduism, Islam, and Buddhism side by side, reflecting a deep-rooted tradition of faith, tolerance, and shared cultural heritage in Assam.

Q: How did Hajo get its name and what does it signify?

A: Hajo was named after Koch Hajo, a tribal chief, and the name derives from words meaning ‘high place,’ which reflects the town’s geographical features such as hillocks and scenic water bodies that contribute to its serene and spiritual atmosphere.

Q: What is the historical significance of the Hayagriva Madhava Temple in Hajo?

A: The Hayagriva Madhava Temple dates back to the 6th century during the Pala dynasty and has been reconstructed and preserved by various rulers, symbolizing Hajo’s long-standing religious importance and its role as a centre of devotion for Hindus.

Q: Why is Hajo considered a shared pilgrimage site for Buddhists and Hindus?

A: Hajo is sacred to both Buddhists and Hindus because they believe Gautama Buddha attained nirvana there, and it houses the Mahamuni Buddha idol, making it a rare spiritual confluence of the two faiths.

Q: What are the architectural features that reflect the cultural diversity of Hajo?

A: Hajo’s architecture showcases Hindu, Buddhist, and Islamic styles, with Hindu temple sculptures, Buddhist motifs like the elephant carvings, and Islamic elements such as Mughal-style carvings at Poa Mecca, illustrating its rich cultural tapestry.

Q: Why is Hajo called Panchtirtha Nagari?

A: Hajo is known as Panchtirtha Nagari because it houses five important Hindu pilgrimage sites: Hayagriva Madhava, Kedar, Kamaleswar, Kameshwar and Ganesh temples.

Q: What festivals are celebrated in Hajo?

A: Major festivals in Hajo include Janmashtami, Dolotsav, Magh Bihu, Shivaratri and the Urs festival at Poa Mecca, attracting devotees from different communities.

Q: Who built Hayagriva Madhava Temple of Hajo?

A: The Hayagriva Madhava Temple in Hajo was originally built during the Pala dynasty, around the 6th century CE, according to historians.

Later, in 1543 CE, the temple was reconstructed by Koch king Raghudeva after the earlier structure collapsed. Subsequent Ahom rulers, especially Pramatta Singha and Kamaleswar Singha, carried out renovation and expansion works, helping preserve the temple and enhance its religious importance.

Q: Who built Poa Mecca?

A: Poa Mecca was built as the mausoleum of the Sufi saint Giyasuddin Auliya. After his death in 1344 CE, the shrine was established at Hajo. Later, in 1657 CE, during the reign of Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, a mosque was constructed there by Lutfullah Shirazi.

Q: Why do Buddhists consider Hajo as a holy place?

A: Buddhists believe that Gautama Buddha attained nirvana at Hajo. They worship the Budha Madhava idol at the Hayagriva Madhava Temple as Mahamuni Buddha.